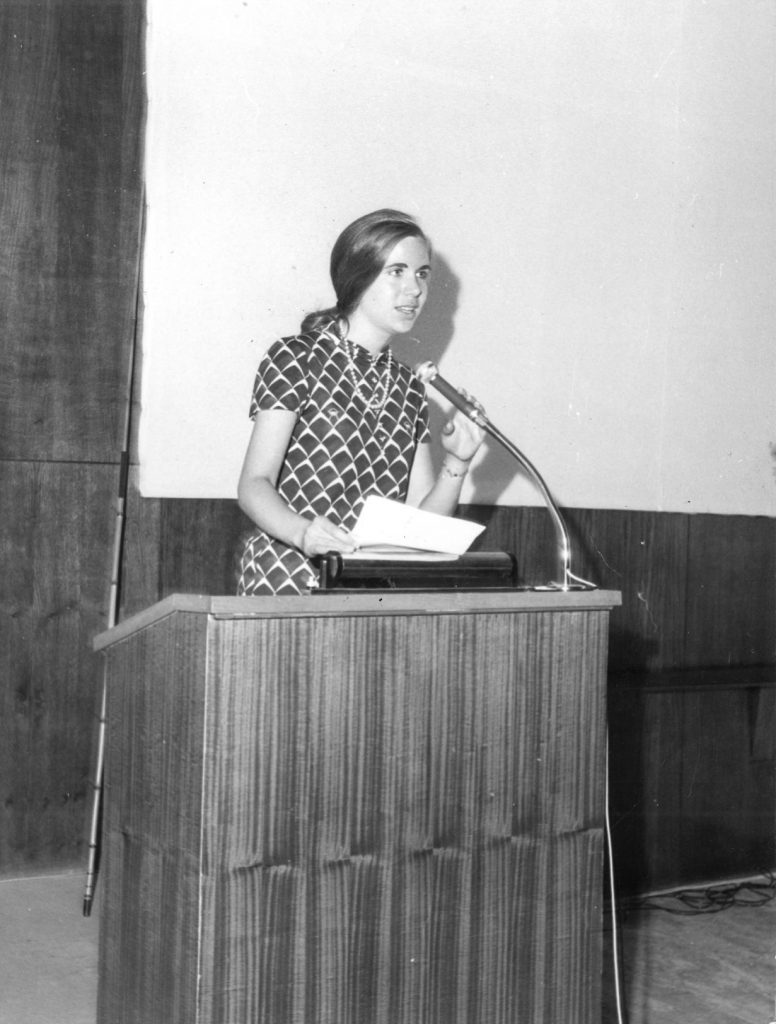

First talk, Budapest, International Society for Neurochemistry, 1971. I dropped the papers, but had already read them. I still have the dress.

For some insight on the type of work that I did over the years, see my Google Scholar pages.

Rita: Stories from my perspective

I had an unusual window into the life of Rita Levi-Montalcini for an exciting period of time. I married into NGF and into Italy. It changed my life in many ways and still influences me today.

For the narrative below, articles are not referenced in detail, but are taken from her books and letters, news clippings, plus personal experiences.

In Praise of Imperfection by Rita Levi-Montalcini (in Italian and English)

Cantico di una vita by Rita Levi-Montalcini (letters)

L’asso nella manica a brandelli, Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini’s Personal and Scientific Journey:

Those who knew Rita during the middle and later phases of her career may have seen only the elegant woman with upswept hair, wearing a silk dress with pearls accompanied by a gold pin and ring designed uniquely for her. If scientific competitors in the new field of nerve growth factor (NGF) research, they may have felt a chill of criticism from the woman who started it all. This latter was eased in later years by the realization that she herself was responsible for all of the scientific interest in NGF and growth factors. No one word can describe Rita (as I was once asked), but many can: joy and passion for science, compassion, duty/devotion, trust in her friends and colleagues, loyalty, grace, graciousness, kindness, generosity of spirit, and a strong sense of equality and fair play. The photo of Rita at age 11 reveals the thoughtful, intellectual nature that led to her rich scientific life and eventual success. (photo)

In the frontispiece to her book of letters “Cantico di una Vita” she quotes from the Old Testament, “I found that which my heart was searching for, I grasped it and will never let it go” (Cantico dei Cantici III, 4), a quote which is not commonly used in a general sense. She described this as a “joyous state of mind” from her work and life experiences.

Rita was responsible for these milestone discoveries: programmed cell death, a practical tissue culture system for experimentation, discovery of NGF protein, and immunosympathectomy, the first knockout model. We should not forget.

Rita was born in 1909 in Turin, Italy to an upper class family, which did not value academic education for women. Her father Adamo Levi finally acceded to her pleas to pursue a career in medicine. She needed to quickly catch up on her missing knowledge of Latin, Greek and mathematics before beginning medical school. When Rita was abroad, she wrote almost daily letters to her mother and to her sister Paola. During her life, she demonstrated her deep love for her mother. Yet, with publication of her memoir “In Praise of Imperfection”, she overcame the mixed feelings about her father to devote a significant section of the book to his praise.

When Rita began to work with Professor Giuseppe Levi of the Department of Neurology, she realized that her true interest was not in life as a physician, but as a research scientist. Her studies on the development of chick embryo spinal ganglia with Levi, were the foundation of the work leading to the discovery of NGF. Using quantitative analysis of silver stained specimens, she predicted that neurons grow and develop, but then, some will die. During this period, her colleagues in Levi’s group included Salvador Luria and Renato Dulbecco, both from Turin, and both eventual awardees of a Nobel Prize for their research.

When the Racial Manifesto was issued by the Italian government on June 15, 1938, Rita and other Jewish coworkers could no longer work at the University in Turin. After a brief sojourn in Belgium, ended by Nazi invasion, she chose to go into hiding in the Tuscan countryside. The stories of working in her bedroom with a microscope and homemade instruments are well known, as is the tale of utilizing “more nutritious” fertilized eggs requested from the local farmer so that she could continue her studies of neuronal development in peripheral ganglia.

After resuming her post at the University of Turin, she briefly joined the Istituto Zoologico of Naples, known for work in developmental biology of marine invertebrates. The letters during this period showed her joy in her work and in life, including strolls with Giuseppe Reverberi, and reading in the extensive library in between experiments. Some days they would take one of the institute’s fishing boats to Ischia or Capri to collect floral and marine fauna for the laboratory, also spending time swimming and enjoying the sea.

During these years, Viktor Hamburger at Washington University in St. Louis had noticed her work. It intrigued him that she had described neuronal cell death as a normal part of ganglion development, not in line with his hypothesis. He invited her to join his laboratory to resolve differences, to determine the mechanism governing the differentiation of motor and sensory neurons destined to innervate the limbs in chick embryos. The journey lasted, not six months, but 30 years.

The research first utilized in vivo models in chick embryos. To mimic Hamburger’s experiments with amphibian larvae, in which he extirpated a limb or transplanted supernumerary limbs, and then observed changes in the ganglia innervating these regions, tumors were transplanted to the chorioallantoic membrane of the chick. Surprisingly, hypertrophy of the ganglia was observed, with nerve fibers reaching to the implanted sarcoma 180 tumors. Rita realized that in order to determine whether this effect was due to having a larger physical “field” of innervation or to the presence of a soluble factor, a new approach was required. She traveled to the laboratory of Herta Meyer in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which led to the development of a tissue culture system that would permit testing of these hypotheses. They developed the plasma clot, inverted tissue culture of neuronal ganglia used for many years, even for assaying the purification of the NGF protein, the molecular factor eventually discovered. This method was one of the first tissue culture models useful for routine experimental investigation.

When the biochemist Stanley Cohen (co-Nobel) joined the Department of Zoology, a new phase of the research began. Facilitated by Rita’s new assay, Stanley set out to determine if the nerve outgrowth observed with extracts of sarcoma 180 was due to a protein, nucleic acid, or other molecule. Snake venom DNase was routinely used to digest DNA present in a sample. To great surprise, this enzyme preparation, crude by today’s standards, appeared to increase nerve outgrowth in ganglion cultures. Further experiments showed that snake venom itself contained nerve growth promoting activity, and that this activity was due to a protein molecule. The presence of the activity in snake venom also suggested that it might be present in mammalian salivary glands, related to venom glands. This proved to be the case, and the growth promoting activity, now called NGF (nerve growth factor) was found to be abundant in male mouse salivary glands. This productive collaboration led Stan Cohen to declare: “Rita, you and I are good, but together, we are wonderful.”

Beyond identifying a crucial source for purifying NGF for in vitro and in vivo biological studies and for chemical characterization, the mouse provided an essential model for understanding NGF biology. Injection of mice from birth with NGF produced hypertrophied sympathetic nervous systems. Production of antisera to NGF soon followed. Injection of antiserum into newborn mice as they developed, led to suppression of the sympathetic nervous system. This was the first biological knockout mouse experiment.

The sheer beauty of the semi-quantitative NGF bioassay almost made the work seem a fantasy. The novelty of the hypotheses and observations were so surprising to some scientists that it took time for the field to become established. This skepticism can explain the sensitivity that Rita felt to criticism and competition. (photo of neuronal halo in culture)

Cohen observed that the mice injected with NGF preparations opened their eyes several days early. This led to his discovery of epidermal growth factor (EGF) in the salivary gland, and to the beginning of this field of study. Rita continued working on the mechanism of action of NGF with a variety of collaborators, including Pietro Angeletti (Piero), Pietro Calissano, Luigi Aloe, among others. She supported the work of this author on the chemical determination of the primary and secondary structure of mouse and snake venom NGFs, together with Ralph Bradshaw. The productive work continued in her laboratory in St. Louis as she gradually returned to Italy to work.

Rita Levi-Montalcini at age eleven.

© Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation, P Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini at first NGF symposium, April,1986 Monterey California, photo by RHA

Work and Life at Washington University in St. Louis:

When Rita arrived in St. Louis, she worked in Viktor Hamburger’s laboratory to pursue their joint project. She found a small rental apartment at first, and enjoyed talking with her landlady every evening after work. As time went on, and her project flourished, Hamburger gave her free rein to continue the work on NGF independently. He offered her a position as lecturer in Zoology. She enjoyed the spirit of the American students, casual, often greeting her with a “hey, doc,” but interested in learning from their professors. In letters to her sister Paola, she explained why it would be difficult to return to work in Italy. She was not interested in becoming a departmental chair, nor in returning to work for Levi in Turin where she would be at the mercy of an eventual, unknown successor. Positions with the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) were few and poorly paid. This situation made it more attractive to remain in St. Louis, where she could work more effectively, and, with joy. Her colleagues Luria and Dulbecco also chose to follow scientific and academic careers in the United States.

Daily letters to her family and frequent trips to Italy were her links to home. In St. Louis, she beautifully decorated a faculty apartment. Rita had many friends. She would prepare wonderful dinners for her guests, whether famous or not. She took pride in her cooking, but because of her devotion to her work, would prepare as much as possible of her food in advance. Dinners at her home started with appetizers in the living room, usually Belgian endive with crème fraiche and caviar, with the Turinese aperitif Punt e Mes. Her entrée of filet en chemise was accompanied by gnocchi di semolina, salad and vegetables, followed by fruit and cheese. She made zabaglione ice cream herself, preparing 4 dozen filled champagne glasses that she kept in her ample freezer, ready for an impromptu dinner party. She roasted her own beans for coffee. Conversation was always lively, and guests departed late in the evening. She later noted that her large dining table was also important in her writing and in preparation of work that led to the Nobel Prize.

Work and Life in Rome:

The opportunity for Rita to return to Italy presented itself when she met Piero Angeletti while he was working at the Washington University Medical School. He had a position in the Department of Biological Chemistry at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) in Rome, and suggested that she could transition her work there. She requested only a microscope, microtome, knives and slides from the Director of the ISS. Rita would spend a few months a year in the lab in Rome, and wrote research proposals to the CNR to support NGF work in the guest location at the ISS. Eventually, she settled into Rome again full time. With her colleagues, she submitted research proposals each year to the CNR. It might be 9 months before the funds arrived, for those not working directly for the ISS. Scientific staff would receive their back pay, regular paychecks for a few months, and then the process would begin again. The devotion of these scientists to Rita and to NGF research inspired. This situation was untenable in the long term, so she worked with colleagues to establish the Laboratorio di Biologia Cellulare (LBC) of the CNR, and the eventually, to create the European Brain Research Institute (EBRI). This provided stability to the scientists. Notwithstanding, this unusual time of financial instability was also one of the most productive and exciting periods of her work. In the labs in Rome, she became “la professoressa”, no longer “doc.”

When Rita settled in Rome, she lived with her twin sister Paola, an artist whose studio was in the adjacent apartment. She called Paola “Gioia” (Joy), in their everyday conversations. There was no longer a need to write daily letters to her, nor to anxiously await her letters. There were many dinner parties at their home, for friends, colleagues, and fellow scientists who came to visit Rita in Rome. Rita no longer cooked. In fact, no one believed that she was indeed an exceptional cook. Entering the pathway to her home in viale di Villa Massimo, the scent of jasmine along the walkway in the summer was an invitation, and the signal of pleasant hours ahead.

Rita in the Laboratory:

Rita herself expressed her attitude toward her research. “It was not work.” She felt “a joyous state of mind in every moment of her days.” Describing the research leading to the discovery of NGF, she said that “I seem to be a truffle dog. In this moment, I sense the odor of the truffle and rapidly dig in the direction of the smell. It isn’t anything special. However, the solution to a problem that has absorbed me for some time, and that the others have overlooked” lay ahead.

When alone, Rita thought about present and future experiments incessantly. She took great joy and inspiration in planning experiments and discussing results with her close colleagues. Discussions took place not just in her office, but in the laboratory, with all working intently at the bench while listening. When her guests at dinner were her daily colleagues and/or other scientists, art and social issues would be discussed, but the conversation returned to science periodically. If a colleague had dinner together with other friends at her home, she would telephone right before bedtime to plan experiments for the coming days and weeks. Of course, she also telephoned first thing in the morning. Luigi Aloe described Rita as a “hurricane” entering his life.

Social Justice:

Rita’s consuming passion for her work did not blind her to social inequities. This was exhibited in both large and small ways. She was appalled by segregation in America, and kept a poster of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the wall behind her desk at work. When she was asked, she said that she had marched with him. When she became a Senator for Life, she took her job seriously, advancing causes important to her. After winning the Nobel, she established a foundation first for Italian students, which later became a foundation in support of Ethiopian women. She wrote books to inspire Italian young people, and spoke out to them as she could. She called for “educational resources for the survival of mankind,” and a “life of commitment.”

While Rita’s dedication to important causes is well known, it was not so well known that she helped many individuals. More important, she treated everyone she worked with and everyone she met with dignity and as equals. She would include her driver at guest lunches with seminar speakers. Those who worked with Paola on her artistic creations were treated as family. Indeed, she left a portion of her estate to some of her “family” who had worked with her and with Paola for many years.

Celebrity:

There is a cultural difference in appreciation of science and scientists between Italy and the United States (at least). After the Nobel, Rita became a celebrity in Italy, not just with scientists and students, but with hairdressers, shopkeepers and most citizens.

After a seminar at the CNR laboratory outside Rome, her driver drove Rita, Pietro Calissano, and the speaker (myself) to a lovely garden restaurant, which was almost empty in mid-afternoon. She included her driver at the luncheon table. Rita ordered rice with a little olive oil, and the others ordered their preferred dishes. Not long after ordering, a procession of food emerged from the kitchen, with portions of each dish ordered for all. The cook and owner entered at the end of the parade to greet her. Food was presented as love for Rita.

At the time of her 100th birthday, the outpouring of emotion and respect for her expressed was stunning. The bookstalls in Piazza Navona had all of her books. The rest stops on the Autostrada del Sole featured her books. When she died, thousands in Turin turned out to honor her.

The First NGF Symposium:

A first international symposium on NGF took place in April, 1986 in Monterey, California. It was organized to honor Rita on the occasion of her 75th birthday, although the festivities finally occurred on her 76th birthday. The meeting celebrated the birth of the new fields of NGF, growth factors, and neurotrophic factors. In the past, Rita had tensions with scientific colleagues and perceived competitors over the fast pace of developments this area. Through the scientific presentations and joyful social interactions at this first symposium, she realized how valued she was for her groundbreaking work in establishing a completely new area of research. Fences were mended with colleagues; old and new friendships flourished. The sense of being threatened by so many new colleagues entering this research field was replaced by the respect and esteem they gave to her. Later, all were happy to have honored Rita before her recognition by the Nobel Committee. This event was a genuine expression that she profoundly appreciated.

The Nobel Prize:

In 1986, Rita Levi-Montalcini and Stanley Cohen were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This type of honor is life-changing, even for someone as well-known as Rita. She experienced the perils and rewards of even greater fame.

An immediate result was a deluge of well wishes. Every day, mailbags of correspondence arrived at her home and office. Rita was a prolific letter writer. However, in the face of the extravagant amount of good wishes proffered, she became depressed at her inability to answer each letter personally, as was her habit.

An unpleasant aspect of the Nobel award was the furor created by supporters of Viktor Hamburger, her mentor and colleague, who had not been included in the award with Rita and Stanley Cohen. Viktor and Rita were close personal friends as well as colleagues. While it is understandable that a great scholar and gentleman such as Viktor should be so admired (including by myself, who was an undergraduate student), the Nobel Prize was clearly stated as an award for the discovery of growth factors, not of NGF itself. There is an extensive literature dissecting the development of the NGF story, beginning with the work of Shenkein and Buecker, to determine who was the most meritorious and seminal in the NGF discovery. However, Viktor gave Rita wings to follow the project that she had started on her own and with him. Stanley Cohen joined with her, and together they launched this field.

Even as late as the occasion of Viktor Hamburger’s 100th birthday celebration, there was bitter protest against Rita. During the dinner, among those standing to make laudatory comments were too many complaining about the 1986 Nobel Prize. The next day, I called Viktor, who immediately invited me to his home to visit. Just before I arrived, Rita had called him to tell him of the death of her twin sister Paola, with whom he also had a close relationship. This underscores the love and respect in this friendship, belying the furor raised by so-called Hamburger advocates.

The President of the Republic of Italy designated her as Senator for Life, although not until August 1 2001, an honor bestowed upon citizens for extraordinary social, scientific, artistic or literary contributions. She was among those who took her obligations seriously.

Rita wanted to inspire and leave gifts for the future. In 2005, she established the Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation first for support/encouragement for Italian young people, and finally for education of young African women at all levels. The web site still exists, but activities have been temporarily suspended. She work books for both causes. Also in 2005, she founded the European Brain Research Institute (EBRI). Although it still exists, funds and leadership are required for carrying it into the future as she wished.

Message to us from Rita on her 100th Birthday:

I was privileged to be a guest in Rita’s life, both scientifically and personally, and I learned from both. I worked with her in St. Louis and Roma – first in the lab in the basement of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, and for a few years in the temporary Laboratorio di Biologia Cellulare outside Piazza del Popolo.

On the occasion of Rita’s 100th birthday, celebrations were held by the ISS and by the government of Italy at the Campidoglio. The day at the Campidoglio was highlighted by a symposium of scientific colleagues. Rita gave opening introductions. She listened intently to each speaker without taking notes. She asked questions of each, and at the end, she gave a succinct summary of the highlights of each talk. We must listen, stay alert, contribute.

After a dinner in the countryside outside Rome, Rita found time to spend a few minutes with individual guests. To me, she asked: “Do you still have the same passion for your work as always?” “Yes”, I replied. Then, “how old are you?” After the response, she said: “you still have 35 good years to contribute.” Yes, we are not supposed to stop trying to make the world a better place. And, indeed, she did write a book about it. Old age should be the “most serene (time of life) and no less productive than earlier stages.” The use of the brain does not cause it to deteriorate as other organs or muscles do, but instead, reinforces and develops qualities that remain undeveloped earlier in one’s travels through life.

RELATED STORIES

Ambiance and Play

The first time that I entered the apartment of Rita and Paola, it wasn’t quite finished.

I didn’t know Paola very well, but Piero and Paola had an engaging relationship. Paola was laying a black and white abstract mosaic design on the terrace. Piero would slip out the doors, and rearrange one or two small tiles to see if Paola would notice. She did, but it might take her a few hours.

The wall opposite the entry had a large nook with great windows. Rita filled this area with many plants large and small, just as she had in her apartment in St. Louis.

A process was underway to select the wall colors in all of the rooms, particularly the living and dining rooms. In the end, each was a slightly different shade of gray or mauve. Much work, but very soothing.

The Youngest Person, Asleep in the Room

I had nothing of significance that I knew how to say, so I said nothing.

Once people know that I lived ca. eight years in Italy, they asked if I had traveled here and there — the answer was, surprisingly to them, “No.”

I was working on my thesis research during the first years, married to a workaholic with strong ties to one place, while accommodating to living in Italy, and learning Italian.

I did experiments all day. I learned some work and daily living Italian from Piero’s technician Constantino Cozzari, also from Umbria.

In the evening, after working at science and learning Italian, we often went to dinner at Rita’s. Sometimes other friends were there, too, or a visiting traveler.

Before dinner, there were antipasti and aperitifs and conversation. One part of learning a language orally is discriminating the spoken word. Rita spoke so quickly, and seemed to me not to breathe between sentences. The conversations were intense.

Dinners were always delightful, and there was more conversation after dinner. At this point, although I was the youngest in the room, I would often nod off to sleep. Concentrating all day on science, Italian, understanding and making myself understood – I was quite tired.

Coffee & Science: First Light to Midnight

Leaving Rita’s house, we drove down via Salaria or via Medaglia d’Oro up to Monte Mario. The first thing that Piero did was make a cup of coffee. Then, Rita would call and want to talk about experiments as long as possible. Rita would call as early in the morning as she thought it possible, to talk about experiments and the day. In the lab, they would talk throughout the day. Close friends that they were, this routine may have encouraged Piero to leave basic science for industry.

Gnocchi di Semolina: From Piero to Ruth to Rita

I had learned to cook for my family when I was twelve years old, but my repertoire was Midwestern limited. The first year that we were married, we lived in an apartment in Clayton, just above the apartment of Nica Attardi and her son Luigi. In a surprise move, Piero offered to teach me how to make a new dish, gnocchi di semolina. With a large pot, a box of Cream of Wheat (semolina) in one hand, and a half gallon of milk in the other, he got to work. Lots of butter, fresh grated Parmesan cheese. After spreading the thick mixture on a surface to cool, we cut it into shapes, round or diamond shapes. These were arranged on a baking sheet, then sprinkled with more cheese before baking.

This was the only dish that I learned to make at that time that really pleased Rita, so much so that she began to feature it at her dinner parties in St. Louis, and later, in Rome.

Via Romagnosi: The Struggle for Leadership

After years of being guests at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), the lab was on its way to becoming an official laboratory of the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR). Temporary quarters were rented in a new building at via Romagnosi, 18A. After moving in, research continued, without the cushion of the extensive resources of the ISS. Two other labs joined with the neurobiology lab to create the new center.

Rita wanted Piero to lead the center, or at least the laboratory, but Piero was still employed at the ISS, where he spent much time, plus he began to spend more time consulting with Merck. He did not always show up for meetings at via Romagnosi when expected. When he was late, Rita would often vent aloud. If I were in the group, I would press my back against the door frame and just wait until it was over. Some years later, I understood that she was mourning the loss of not just her collaborator, but her close friend. I just happened to be there.

I arrived home by myself one late summer afternoon, and heard a knock at the door. Corrado Baglioni and Glauco Tocchini-Valentini were there, asking where was Piero, and when would he be home. I had to let them into the foyer. I eventually offered them water. But, they kept asking about Piero’s whereabouts, which I did not know. They remained in the foyer, pacing and fussing for about two hours before eventually resigning themselves, and leaving. This episode was frightening for me as a young woman scientist. I understand that they were fighting for control of the CNR leadership. Baglioni was likely looking at his last opportunity to return to work and live in Italy. I could not help.